For My Father, Tim Enright

I will tell this as it was told to me because that is how the real stories are passed down. In Listowel, Ireland, Timothy Enright, my father’s grandfather, was a cooper, a red haired man so wild in drink that it took seven guardai to drag him to the station to cool off. Inebriated, he drowned in a puddle, leaving a widow and five children. The youngest, Paddy, was taken off by the authorities as it was deemed she had too many to look after. His oldest son, Jack Enright, with his friends, always known as ‘the boyos’, took the King’s Shilling, all aged fifteen, to go to the fair. They hid out in the fields but the recruiting sergeant caught up with them the next day. All three went through the entirety of the First World War, as privates, in the worst of the most famous battles. There’s a picture of them in uniform, Jack with a young full face and a conceited look, right in the front. All survived it, although Jack had a head shell wound which, when his children felt it, showed the furrow ploughed into his bone. His hair had been red brown, in all later pictures snow white.

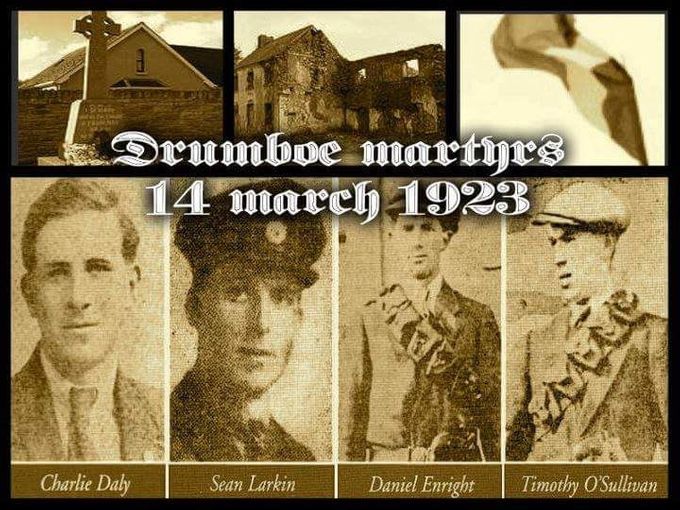

When he returned, he was immediately interned, as his younger brother, Daniel, being caught and betrayed in a farmhouse as one of the Flying Columns of the IRA, was imprisoned along with his companions. They had a revolver and one German Egg Bomb. They were not expected to die but were executed in reprisals by the Free Staters. I have read Daniel’s letters; simply expressed and pious in the way of the time, he asked his mother to look after little Nellie, his baby sister, until he saw them all again. Of course, he never did. They were four of the seventy seven killed then. There is a song about the four of them, ‘The Castle of Drumboe’, the one my father sang starts with this line, sung by Dominic Behan when I found it,

"The midnight hags are shrieking round the castle of Drumboe".

Jack was on hunger strike in the camp, along with others, and when the news came, the newspaper was passed around amongst them, and they would not show it to him.

Afterwards, he and the boyos returned to work. He to a woodyard. He married my grandmother, Elizabeth Sullivan, who had come from Killarney but would never really tell of what had happened to her. The only one she spoke to was her daughter, Mai, whom she told that her mother had been a schoolteacher but she died and when her father remarried, the stepmother, having neglected her younger brother, the boy died of tuberculosis. Jack and Lizzie had four surviving children. One died at birth. My father remembered this as they all lived in ‘the house at the back’, a one roomed shack with a tin roof the rained dinned on, and the children were only divided off in their single bed together by a curtain. It was hushed and people made a little box to take the deceased child away in. There was no money for a burial.

My father remembered his father talking and talking at night about the war and my grandmother would say,

"Oh, not the Somme again, Jack.”

When he came in from the pub, he’d say,

“Do you see these little feet, Lizzie? They’ve travelled the worreld.”

Like most, he was a batterer when drunk and when my father was seven, he took up the lump hammer and went at his father with it, telling him that if he ever struck his mother again, he would kill him. He never hit her again. After that, in a way, my father took on the head of the house role. There were things he regretted. Little things. His father used to paint the hearth red at Christmas and draw bricks on it. My father started doing it and he always felt he’d taken something away there that he shouldn’t have.

As a child, brought up so Catholic, he was a very religious boy. He remembered peeping in the door of the big Protestant church in the square and thinking he’d go to hell for it. He was bright and so, when it came time to leave school to work, the owner of the woodyard said he’d pay for him to stay at school because if you train up a priest, you’re getting a place up there, after all. He was not meant to play with a certain family because they were a TB family but he befriended the boy, a fat lad, strangely, and went there regardless. If he brought it back or it was there anyway, who knows, but in her later life, my aunt learned that she had TB scars on her lungs. There was a younger sister in that family, who got pregnant as a young girl and died in childbirth. The nuns and the priests would not have her buried in their consecrated ground.

It was then that my father finally turned from the Catholic Church and all it stood for. In his last years he kept seeing her, standing on the corner, barefoot in rags with her elf locks blowing in the rain, so poor and so cast out.

They were all poor, no shoes as children, and if there was an egg, the children took turns to have the top of it, as that was for the working man of the house, his father. His father’s health was ruined by the war and by the hunger strike but he worked on at the yard, with only a sack over his shoulders when it rained. My father had to take his books out into the field to study as there was nowhere else and he was told,

“Get out there, boy and get some fresh air,” by his mother.

In school now, he was passing on his reading, James Connolly, Karl Marx. There was of course, only one outcome. The priest headmaster called him in, beat him for it and expelled him. So he went to work cutting turf and being my father, immediately tried to organise them all into a union to protest against bad wages and working conditions. They were all sacked.

Paddy had returned only once. He had ended up, from the orphanage, in England. My father recalled him at the half door, with the black curls his father’s other dead brother had had. Paddy, as far as was known, had been in the RAF and he had sent money back to his mother but she burnt it as being blood money, poor as they were because, as she saw it, it was English money, tainted by the death of Daniel.

My father had many childhood friends and at this point he went on a bicycle tour with one of them, Jim Kennelly but poor Jim suffered from what was commonly known as ‘the nerves’ and had some kind of breakdown. He went missing and my father found him naked riding a cow in the field. Everyone went to Killarney for the nerves. Jim later went to America, where he was a policeman in New York.

After this, again tutoring the woodyard owner’s son, who had not given up on him, my father was supported to apply for a scholarship to go to Trinity in Dublin, to read English. Having got there, he instantly decided to campaign as an MP for the restoration of the Gaelic language. He didn’t win but he had a very good tutor who insisted he must not throw all away and take his exams. He did so a year late and got a first, with the top marks in the whole of Ireland. He could not get any work there, though, due to his politics and so, he too, went to England.

I have said that he had many friends, some quite famous, Eamonn Keane being close to him but for me there is always one who will still be at his side. If you go to Listowel, to the old handball court where the boys played and pull aside the ivy on the bridge, you may still see, as I did years later, in big, black dripped tar letters,

‘Tim Enright, Jim Kennelly’.

Share this page